Extrication Tips: Instilling confidence with simplicity

Chad Roberts

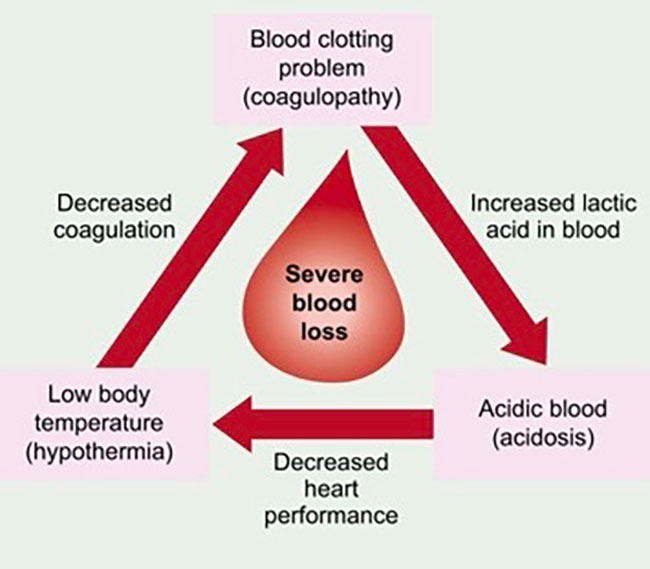

Features Auto Extrication This depiction of the Lethal Triad of Trauma simply shows the circling effect it can impose on our trauma patients.

This depiction of the Lethal Triad of Trauma simply shows the circling effect it can impose on our trauma patients. I recently read that “complexity creates chaos and confusion.” While I can’t entirely remember its source, the meaning of the statement has stuck with me and drove the topic of this column, which is first on scene trauma patient assessment. I’m not talking about the acronyms we have been ingrained with from day one, but a more simplified approach to the fire service’s role in initial patient care. Our roles in multi-vehicle accidents should not start with tool selection and moving metal, but more importantly towards making quick decisions that will ultimately have the greatest outcome on our patient’s chance of survival.

To accomplish this task I felt it was necessary to question one of the best I know in the industry. And through my years of competition and getting to know people all over the country I felt it would only be fitting to reach out to Mike Tesarski. He is a captain for a full-time Greater Toronto Area department, a flight medic for over 20 years, has been involved in the extrication competition world for many years and plays a major role in the trench and technical rescue sector across the country. All of this is just the tip of the iceberg and why I felt he was a great source for what I am trying to create for our service; a simplified approach to our first on scene trauma patient assessments.

While talking with Tesarski I came up with a series of things we should most importantly be surveying and evaluating. The first and foremost being an overall assessment of the incident. Being able to read what actually happened, how fast and from what angles can play a huge part in assessing our trauma patient. Being involved in an open highway incident can have much greater impacts than one in town. Being involved in plane crash can produce much more severe injuries than a small accident in a parking lot. Take the words out of your patient’s mouth and survey what you think is severe. Our trauma patient may seem totally fine, talking and walking. Don’t get trapped into that. If the incident looks bad it probably is bad for them —they just don’t know it or may not yet. Shock and the body’s response can do crazy things. As rescuers we have to read the incident and anticipate what could happen. Take a look at the inside of the vehicle as well. Is there intrusion from the crash and where? Steering wheel or pedal deformity? The collection of all this information must be something we are keeping mind and drawing our own worst-case scenario from for our trauma patient.

Our next step comes with questioning our patient, most importantly on what they remember. Do they remember the incident? Lose consciousness? Where were they going? What day of the week is it? What hurts or is entrapped? These are all key questions to get an overall early impression of our patients, and revisit these questions again to confirm or judge if conditions are worse. If they struggle with some or all of these questions we have to immediately assume we may have an issue. Whether it is because of the incident or maybe the cause, we need to get a baseline level of consciousness for our trauma victim.

ABCD: Although this may seem simple, it has to be there. There is no magic trick here, our baseline airway, breathing level/quality, overall circulation/bleeding and deformity must be performed right after we get a good idea of their LOC. While talking with your patient you are able to gather the A/B pretty quickly. For circulation, we need to go beyond pulse checks. Skin colour and temperature, as well as any gross bleeding are just as important as a pulse check when assessing our trauma patients. And lastly, deformity. Like we mentioned in the first part of the assessment, read the overall scene. Just because we cannot see a deformity, the condition of the vehicle/speed and types of vehicles involved can give us some key clues to our patients underlying injuries.

Time is huge and it is something that often gets away from us. There is a common theme in all the extrication competitions I attend. They are always timed and that is for great reason. Just like any major incident we attend in the fire service, time is key. Knowing when we hit that roughly 20-minute mark can be a great indicator for where we are at with our incident. The greatest place for any of our trauma patients is in an emergency room, so knowing when to make the call to remove a patient quickly and with a little more force will far outweigh the minor injuries or pain that we may inflict while doing so. Our very capable medics can fix pain and minor issues, but we can’t stop bleeding in the car or on the way to the hospital. It doesn’t have to be an exact 20 minute stopwatch, but know your on scene times and call your dispatch if needed. Don’t be afraid to stop and call an audible to stop the time from running up.

And finally, one of the most important and overlooked things we can do for any trauma patient: Keep them WARM! Tesarski was the first to introduce me to a condition called the Lethal Triad of Trauma. Very much how the fire tetrahedron is to us as firefighters, the triad of trauma is to victims. Simply put, when our patients are cold their blood flow is restricted, which in turn reduces the bloods clotting mechanisms, which are directly affected by temperature and PH levels (add on blood loss as well and the clotting mechanisms are reduced even further). Without those clotting factors our tissues aren’t properly perfused and can enter into metabolic acidosis, raising the body’s PH level. This delicate electrolyte imbalance can negatively affect the heart’s ability to pump blood, which decreases the body’s ability to thermo-regulate, worsening hypothermia. Add on medications, which a lot of our more elderly population take such as blood thinners and beta blockers that can make a normally elevated/compensating heart rate read totally normal, and you can quickly see how the lethal triad of trauma can become a circling of the drain effect.

This was a guide to some of the first few things we need to accomplish with our trauma related patients and hopefully instill the confidence needed when first on scene. A huge shout out to Tesarski for sharing his knowledge

Chad Roberts is a firefighter in Oakville, Ont. He is a member of the Oakville extrication team and competes and trains across North America. Contact Chad at chadroberts12@gmail.com.

Print this page